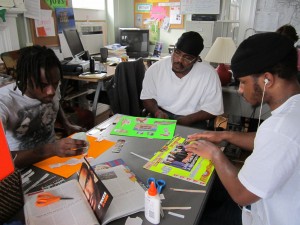

Michael, Lamarzs and Antwan create vision boards as they prepare for their post-release lives.

A unique Washington, D.C. nonprofit, Free Minds Book Club & Writing Workshop, not only inspires young inmates by engaging them through reading and writing. but helps them get their lives together and find employment after being released from prison.

For the past 10 years the organization has worked with youth who are prosecuted as adults in Washington D.C., of which there are about 65 each year.

“They’re in the DC Jail before they’ve been sentenced,” says Tara Libert, the organization’s co-founder and executive director. “Mostly it’s for armed robbery, carjacking, rape, anything involving a gun. They’re in the juvenile unit of the DC Jail. They could be there from a few months to a couple of years. The majority of our kids are there between six and nine months.”

After that they’re shipped out to federal prisons across the nation, since D.C. has no state prison. While in the DC Jail, however, almost all of them join the book club.

Although they’re 16 or 17 years old, on average they read at a fifth grade level, and most of them have never read a book in their lives. They’ve also, for the most part, dropped out of school or had no interest in learning.

Many of the teens’ parents have been absent from their lives, and they’ve raised themselves on the streets. Ninety-eight percent of the young men are black and 2 percent are Hispanic, and they’re locked up for an average of four to six years, between the DC Jail and federal prison.

Program goals

More than 250 youth participate in various aspects of the Free Minds Book Club & Writing Workshop program each year. The program’s goal is to transform lives and help these young men envision their potential and create new educational, personal and career goals.

Free Minds staff members go into the DC Jail and ask new inmates if they’d like to be a member of the book club. Once they join, each new member receives a dictionary and a journal for writing poetry and essays.

Based on the belief that books and creative writing have the power to inspire individuals, to teach them, to build community and to change lives, the organization conducts weekly meetings in the DC Jail where members come together to discuss books that they have read. The books, which have relevance to the lives they are leading, are chosen by a vote. Some of the writers of the books read by the club have attended meetings.

Once they’re transferred to federal prisons at age 18, Free Minds continues to support them by sending books, discussion questions and creative writing assignments. Staff members keep in touch with each member, encouraging them in their efforts and pairing them with a pen pal, who critiques their work and offers support.

Reentry support services

The club doesn’t end with their prison term, however. Once released, members have access to a Reentry Support Program. Free Minds offers a one-week paid apprenticeship in its office, where those recently released from prison learn computer skills and how to use a gmail account, help prepare the book club lesson plans and answer the phones.

They also learn such essential skills as how to show up on time, how to get to appointments and how to call in if they’re going to be late or sick. Interns learn formal correspondence by writing a letter to their probation officer.

“The reason our outcomes are so good is because we’ve known our members since they were 16 and first arrested,” says Libert. “We can achieve a lot in a week. It’s like an assessment week. We call them program assistants and they help with everything in the office.”

During the internship week, Free Minds brings in guest speakers who have been incarcerated and are now working to demonstrate that it’s possible to find employment even with a record. The staff puts on a networking lunch with some of the other nonprofits in the building where the organization is located, so the interns can learn how to network and so they can discover the importance of personal connections.

Although Free Minds hadn’t set out to offer job services of any kind, it decided to launch the internship program about two years ago.

“We were referring them (those released from prison) to vocational training or job readiness, and they weren’t staying or weren’t lasting,” says Libert. “So we said we need to have a time (the internship week) where we can observe them and practice real skills in a supportive employment place where you can make a lot of mistakes.”

Free Minds also does some job placement through referrals from employed members but would like to do more in that area. The organization is currently looking for a strategic reentry partner who can take on the role of dealing with job readiness skills and placement.

For more information, visit http://freemindsbookclub.org